The history of the Iberian Peninsula was rather dynamic during the Middle Ages after the decline of the Western part of the Roman Empire. The new wave of invasions by the Visigoths from the north and east started to spread over the area and forced the change in settlement patterns from the urban sites to the rural ones and the triumph of Christian religion. Girona, which in the Roman period was called Gerunda, was not an exception either. Instead, most of them shifted residential to agricultural regions close to the city called lager, but the city was important for Visigoths hence. The mint for coinage was located here and the provincial council of bishops assembled in this place in the year 517, thus excluding it from having no significance.

The rural setting particularly in this period depicts a general shift in the region from centralised authority as exemplified by the Romans, which dispersed into local powers. This decentralization was accompanied by the development of Christian institutions, which featured as central not only in providing spiritual guidance but also in consolidating the area’s administrative strength. Indeed, when the Visigoths chose to retain Girona as a city that also continued to issue coinage, and as a religious post, they revealed the authorities’ desire to maintain it as a strong economic and ecclesiastical stronghold that would serve to further cement their rule.

This relatively peaceful continuity lasted until the year 715 when the Muslims arrived at Gerunda. The fact that the users of Muslim troops did not meet with any resistance from the people of the city made it rather easy to transfer power. Thus, despite the new masters having divided power with the local nobility and the church, the normal folk did not have a deep concern with the Islamic mentality. This continuity of the local pagan traditions of power and rule was apparent in 785 when the same nobles and churches handed over power peacefully to Charlemagne’s Frankish fighters.

The last period of Muslim domination in Girona can be mentioned as one of the examples of the successful evolution of the city. The local elites’ cooperation kept social order, and continuity was partially possible because the ruling changed, but the people remained the same. This flexibility was important when Charlemagne’s troops arrived; again, the leadership paid a smooth sycophancy to the Frankish administration. Of all elements of Girona’s history, this time period clearly outlines a realistic balance of subjugation and fight for identity to protect the cultural and social organization of the city.

Medieval Walls: From Protection to Limitation

Medieval Walls can be seen in Britain from the 9th to the 15th centuries. Still, Girona, which had officially joined the Carolingian Empire back in 760, did not remain unaffected by the quarrels. In the year 793, the Muslim stronghold was at its weakest as General Abd-al-Malik tried to regain control of some of the provinces which had turned Christian. In the year 827, there was a division between native and Frankish counts on control mechanisms. Such conflicts called for the building and developing of city walls during the Carolingian period. One of the sad cases is the 793 conflict that involved the use of projectiles that caused a considerable impact on walls and called for renovation. These walls remained a constant throughout the years, starting from the structures that provided protection from the enemies in the past and turning into the barriers that limited the city’s growth in the modern days.

It is noticeable that Girona’s wall development went through various phases that might be observed in different cities in general, though more detailed analysis is required in this case. First, requirements of constructing a wall were to shelter people from danger coming from outside or to defend them from enemies. Nevertheless, the same walls posed the problem of growth limitations as the city developed, and thus selective demolitions occurred in the 19th century. This sensible posture ensured that the historically important parts of the city were retained as well as meeting the current demands. Some of the remaining parts from these walls are the Carolingian entrance at Plaça de la Catedral known as Portal de Sobreportes and the remaining part of Mercadal wall in Baluard de Sant Francesc on Plaça Catalunya.

In this sense, the remains of the different walls dating from the Middle Ages allow users to somehow get an insight into Girona’s past. Owing to these walls, tourists can visualize the medieval style of defense in the city, as well as the lifestyle of the people at that time. It is quite usual to observe old and new in Girona’s sociophysical space indicating that the city is keen to opt for the advances while retaining history. The remaining wall sections not only serve as historical landmarks, but they also provide views and add to the ambiance of the old town at several sites, thus improving the tourists’ experience.

The Religious Romanesque: Monastery of San Nicolau de Girona and Santa Pere de Galligants (12th Century)

As it has been observed earlier, the walls of the city also belong to the Christian era; the same appears to be the case with the temples of Girona. Take, for example, the Church of Sant Nicolau featured as a 4th-century Christian funerary enclosure. By the middle of the 12th Century, this spot had evolved into a Romanesque church and had been mentioned as early as 1135. It was meant to perform secretarial tasks in a cemetery that honored a saint known as Peter. In years to come, the cemetery was to be related to another temple often referred to as Sant Pere de Galligants. As of now, Sant Nicolau serves as an exhibition hall, sometimes alongside Sant Pere.

Sant Pere’s history and construction of the monastery date back to the year 992. Nevertheless, the current church structure was occupied in 1131. In the process of this recovery, this church relied on S. Pere quarter, having been wielded by the abbot since the church’s creation until 1339 when Pedro IV of Aragon Alfons reasserted the crown’s rights. Sant Nicolau and Sant Pere are fine examples of the novices of Roman architecture being strictly practical and offering rather simple and unpretentious coatings. Sant Pere also has the honor of hosting the Archaeology Museum of Catalonia in Girona, thus responding to its historical mission.

From a more general standpoint, these are simple Romanesque constructions characterized by a linear architectural style that was popular in this part of the world at the time. In Catalonia, the goal was to have pure functionalism rather than aesthetic extras and a decline for the over-exaggeration of structures. This is ascribable to Functionalism, with regards to the exterior, where one can see that the walls are neat and strong, more like pillar-like structures erected with thoughtful little detailing; and with reference to silhouettes, where the designs of these churches are uncomplicated, explicit more like boxes fitted conspicuously. The incorporation of local materials in the construction as well as the use of locally appropriate construction methods also depicts the aspect of resourcefulness among the people of the region. All that, apart from witnessing to the aesthetic and historical richness of the Romanesque period, these churches succeed in illustrating many of the material aspects of the medieval Catalans’ practical world and their Christianity.

Civil Romanesque: El Call and the Arab Baths

Historical evidence points out that after the year 888, more than twenty Jewish families were inhabiting the central area, that was close to the site of the old cathedral. These families moved in the twelfth century, and their settlement gravitated more or less around Carrer de la Força, which starts at the place where the square in front of the cathedral now is. The name “Call” originates from the Jewish term “kahal,” which means Jewish neighborhood; the same has been used to refer to similar zones in the region of Catalonia. Pujada de la Catedral street is one example, together with Manuel Cúndaro street much more conversing Claveria and others. Able-bodied ongoing cooperation of entities like the Israeli mansion has helped maintain such old provinces. At that time, Girona had about 800 Jews; for more information, there is the Museum of Jewish History on Carrer de la Força.

An even more important civil Romanesque building is that of the Arab Baths located at Carrer del Rei Ferran el Católic. Contrary to the name of these baths, many of them operated more like Roman and eastern bathhouses did. It has semicircular arches, barrel vaults, and Corinthian capitals in line with Roman classical art styles. Based on records, the chapel has been in existence since 1194, though it was reconstructed in 1294 after destruction during the battle of 1285. This conflict emerged after Pope Martin IV attempted to seize properties belonging to Pere III the Great because the latter aided a rebellion in Sicily. Although Girona people surrendered to famine and illness, the bigger war was won.

El Call is the Jewish area of the middle ages, which is evidence of the multiculturalism that was present in Girona. It is for these reasons that the preservation of these areas accentuates the need to accept and embrace multiculturalism as a source of celebration. Again, the presence of Girona’s Jewish community in the 12th century and the later creation of the Museum of Jewish History speaks volumes about the history of Jewish people in Girona. Through the exhibits at the museum, which consist of artefacts and historical records, one can get a full view of the revelation of the society, its achievements, and history, which makes the cultural diversity of the city more colorful.

The Arab Baths are actually a kind of architectural complex, built in Girona that is viewed by many as Mesoamerican by its name, but are actually a result of various civilizations that contributed greatly to Girona’s architectural fabric. Together with national references to the Romanesque art, the construction of baths and the purpose of saunas more broadly highlight the possibilities of the intention transfer between cultures. The complexity of the architectural design of the baths, having been rebuilt after the siege of 1285, says a lot about the inhabitants of Girona and their determination to continue using the important communal halls. These baths are a sign of the level of progression of the city as well as the merging of diverse cultural and architectural periods.

The Cathedral: A Symbol of Girona’s Rich History

The cathedral of Girona is the temple of the diocese of the same name and is considered to be very interesting and cryptic. Overall, there is no doubt that the central temple in Girona was a highly important edifice in the Iberian Peninsula by the year 1000, though, arguably, that is not to say it was always located at the apex of cultural ascendancy in this part of the world: The city appears to have been surpassed by both Toledo and Seville around 600 widely at least. Under Muslims (715-785) this temple served as a mosque for a while. Between the year 908, the pre-Romanesque temple of Santa Maria was to be consecrated. Sadly there is not much remaining from this time, the present form of the cathedral started to be built in the 11th century in the Romanesque architectural style.

The cloister, the Tower of Charlemagne, the altar, the bishop’s throne, as well as the Tapestry of the Creation which dates from the late 11th century or the early 12th century, are remaining from the Romanesque period of the year 1010-1132. The Tapestry is stored in the Museum-Treasure of the Cathedral of Girona to this present day. The Gothic style gave the cathedral a new aspect in 1312 and from that year to 1604 the last stone was laid. Despite the fact that Romanesque elements are dominant in the cathedral’s structure, the Gothic accretions give the building a personality. The construction of the imposed rebuilt nave in 1417 as a single wide nave with a span of 23 meters created one of the largest naves in the world, second only to the nave of St. Peter’s in Vatican.

The style change from Romanesque to Gothic conveys the architectural and cultural development at that time period. The first phase is defined as Romanesque, and it is evident that during the medieval period, there was more focus on defense and hence the thick walls and very little decoration. The buildings that still can be seen today, like the cloister and the Tower of Charlemagne, allow one to get some sense of the architectural and religious practices that dominated the epoch. Contemporary to ‘The Tapestry of the Creation’ is among the greatest medieval arts depicting scenes from the bible along with the evident cosmological features of the given theme.

The Gothic renovation was a clear sign of a new fashion in architecture, which was both more lavish and extended than what had been seen before due to what was presumably the greater demand and means of the period. It was decided to create one wide nave which was daring and totally different from the dark narrow aisles found in medieval architecture; this served to notable the sophistication and integration of the central space. Creating such a space was a great engineering challenge and demanded both the mastery of engineering and the artists’ eye as well as incredible craftsmanship, as the result not only leaves one breathless but inspires awe and spiritual sentiments. Thus we have the Romanesque aspects that represent the solidity and the tradition opposed to the Gothic structures that symbolize lightness and the innovative architecture, therefore the cathedral also is a sign of the history and culture of Girona.

The Initial and Full Gothic: Ruins: The Church of Sant Domènec and The Church of San Feliu (11th-16th Centuries)

A little south of this area of Girona, the University of Girona’s Faculty of Arts now occupies the Convent of Sant Domènec. The constructing actuality of a church and a cloister belong to the late Gothic period of Catalonia, the fourteenth century. In contrast to the organizations of the facades and the encompassing utilization of glass that is so profoundly rooted in different Gothic styles of incomparably several European nations, austerity held a key situation in Gothic constructions of Catalonia. This style has fairly smooth surface, fewer glass jams, fewer pointed ceilings, and both pointed and semicircular arches combined. This was particularly so where structures had a single nave as most of the structures of this early period reflected the pragmatic utility based style that characterized the region’s architecture.

The Church of Sant Feliu is also another popular Gothic church found in Girona. Erroneously known as a Roman temple, it was probably constructed between the 14th and 16th centuries on the site of an earlier Romanesque temple, sharing the flawless beauty and understated Gothic style of a building in Barcelona. The walls and the bell tower erected between 1361 and 1392 are also Gothic but have stronger reminiscences to Northern Gothic. The interior is equally interesting and contains such artistic masterpieces of medieval architecture and sculpture as the tomb of Sant Narcís sculpted by Joan de Tournai in 1328, and the Chapel of Corpus Christi with the statue of the Recumbent Christ which is the work of Aloy de Montbrai created in 1350. Furthermore, eight Old Christian sarcophagus sculptures from the 3rd and 4th centuries give the main idea of shifting from the art of the Roman epoch to the Middle Ages.

Sant Domènec convent and Church of Sant Feliu are classical examples of its uniqueness of the Catalan Gothic architecture. The architecture of the Convent is not luxurious and does not contain many ornaments; it seems that Dawnay’s main goal was to create a sanctuary that could be built quickly and would be practical and sturdy. Since the construction was done in the region where the stress is on the structure, the smooth walls and limited use of the glass windows made it easier to put up sturdy structures. Using sharp and semicircular arches as pointed and round ones guarantee the concordance of a Gothic and Romanesque style.

Sant Feliu vividly conveys the rather aggressive look of the Gothic style, at the same time it has an exquisite and rich appearance of the interior. From a defensive standpoint by 1632 the church had all the functional features that were necessary in a building that, while not quite discreet, did not contradict its clearly tagged aesthetic requirements. As observed, the bell tower has a northern gothic influence hence focusing on the transference of architectural ideas between places The interior furniture is also historical. The early Christian sarcophagi are well decorated and narrated through reliefs which make them a good source of analysis of the early historic and the medieval periods. Combined, they represent one of the most fascinating examples of architectures and a symbol of a people’s heritage.

Getting to Girona

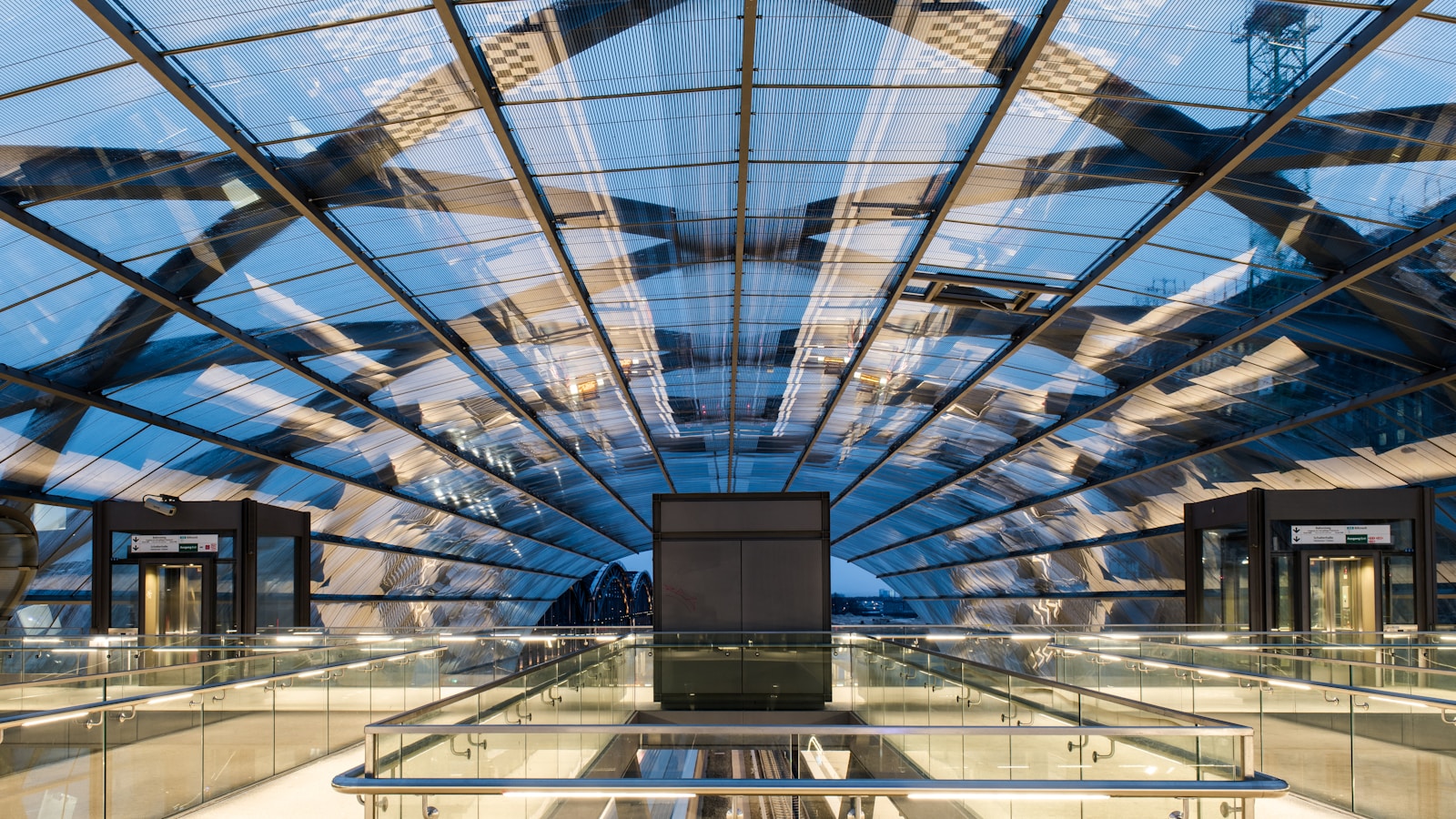

The transportation of preference is the high-speed train (AVE) for going to Girona that is well connected with most of the big cities in Spain. The train station is said to be in the area of Plaza de España and to get to Plaza Poeta Marquina take the Ferrán Soldevila i Zubiburu Street. Here you can use the L5 to get to the Germans Sàbat stop of the subway. This route will lead you to Parque de la Devesa, from there you can go back to the round and cross the Pedret bridge to get to the north of the old town to start the visiting.

This is evident in its station as a stop on Spain’s high-speed train line proving its connection to the modern transport system of the country. Due to the availability of the AVE, visitors from the different parts of the country can get to Girona easily and in comfort. This ease of access is supported by the availability of a good local transport means which enhance the access to the city of Girona. Otherwise, the carefully determined directions and stops help to adjust the transitions from the train station to the important historical monuments without bulky excesses, thus contributing a lot to the valuable experience. The touristic experience from outside the city to the inside of Girona, from the new buildings to the old roads, captures the sound and qualitative feel of the modernity and history in one city.